USC-led research sheds new light on the catastrophic changes resulting from a burst of greenhouse gases and rising temperatures that wiped out most life on Earth and paved the way for the rise of Jurassic dinosaurs.

Tag: Faculty

Eun Sok Kim, Chongwu Zhou elected National Academy of Inventors fellows

The professors in the USC Viterbi Ming Hsieh Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering are among 162 inductees.

‘Try on new identities without fear’

USC Rossier’s Theo Burnes leads discussion on supporting nonbinary youth within educational environments.

How artificial intelligence will disrupt the practice of law

USC Gould’s Jonathan Choi specializes in law and artificial intelligence, tax law, and statutory interpretation.

The reality of COVID-19 learning loss

A new study reveals a surprising parent-expert gap regarding the impact of COVID on the academic well-being of children.

There’s a financial literacy gender gap, and older women are eager for education that meets their needs

Only a small fraction of women have received any financial education at all. A USC expert looks at the situation.

‘Lithium Valley’: Inside California’s ‘white gold’ rush

The Salton Sea holds enough lithium to power more than 375 million electric vehicle batteries. (Photo/iStock)

Science/Technology

‘Lithium Valley’: Inside California’s ‘white gold’ rush

The race to mine American lithium at the Salton Sea is intensifying, but USC experts caution against potential environmental health impacts in a region already burdened by poverty and air pollution.

The Imperial Valley in southeastern California is emerging as a global hotspot for lithium: A new U.S. Department of Energy report confirms that the Salton Sea holds enough of the rare mineral to power over 375 million electric vehicle batteries — more than the total number of vehicles on U.S. roads.

That’s good news for the global shift toward clean energy and American ambitions of energy independence. However, USC experts warn that the race to mine American lithium could come with significant environmental and public health impacts.

“‘Lithium Valley’ is now poised for a potential economic boom — one promoted not just by companies but by environmentalists who believe that the method of lithium extraction being proposed there is the ‘greenest’ approach available,” said Manuel Pastor, director of the USC Equity Research Institute. “But the question is, who will benefit from the boom and who will face continued marginalization?”

California enters the global race to mine ‘white gold’

Lithium — “white gold” — is produced from hard rock or extracted from natural geothermal brines, sourced from salt lakes like the Salton Sea. Australia is the world’s biggest supplier, with production from hard rock mines, while Argentina, Chile and China lead in lithium production from salt lakes, according to the World Economic Forum.

In recent years, both the pandemic and geopolitical tensions have highlighted the risks of relying on foreign sources for critical materials like lithium, nickel and cobalt that power the batteries in our EVs and devices. The World Bank anticipates a 500% spike in demand for lithium by 2050.

“To enable sustainable future production from local resources, the U.S. needs to reduce the amount of lithium used in batteries and seek alternative local sources of lithium,” said Greys Sošić, an expert in sustainability and global supply chains at the USC Marshall School of Business. She points to geothermal brine lithium recovery — a process that extracts battery-grade lithium from natural geothermal brines found in hot springs and salt lakes such as the Salton Sea — as a viable alternative.

Shrinking Salton Sea, air pollution crises raise public health concerns

Originally formed in 1905 as a result of an engineering mishap and spanning 350 square miles, the Salton Sea is now shrinking. Its exposed seabeds are releasing dust that poses a threat to health, especially in children, in a community already beset by environmental and economic challenges, experts say.

“This is one of the poorest counties in California, with a median household income roughly one-third of that in Silicon Valley … and it has a population which is 85% Latino but with political representation falling far short of that standard,” said Pastor.

The childhood asthma rate for the communities around the sea is 22% compared to the national average of roughly 8%, according to Shohreh Farzan, an associate professor of population and public health at the Keck School of Medicine of USC who has been collecting samples of air particles at elementary schools around the Salton Sea since 2017.

“Many children in this area are affected by respiratory symptoms, such as wheezing and allergies, and the local air quality is a likely contributor to the high rates we see,” Farzan said. “The trade-off with lithium is that while it can reduce our reliance on fossil fuels, there is much that remains to be understood about the environmental impacts of the extraction process and whether this energy transition could impact the health of the surrounding communities.”

Jill Johnston, an associate professor in the division of environmental health at USC, adds that “while efforts to move away from fossil fuels and promote zero-emissions technology is important for public health, it is critical to avoid creating new environmental hazards. The overly burdened families near the proposed lithium extraction site deserve to have clean air and water and protection of their health.”

USC Viterbi team explores medical wearables — custom sensors for affordable medical diagnostics, environmental monitoring

Researchers are using embroidery and lasers to create cutting-edge sensors for wearables and personalized health care.

World-renowned architect Brett Steele named new dean of the USC School of Architecture

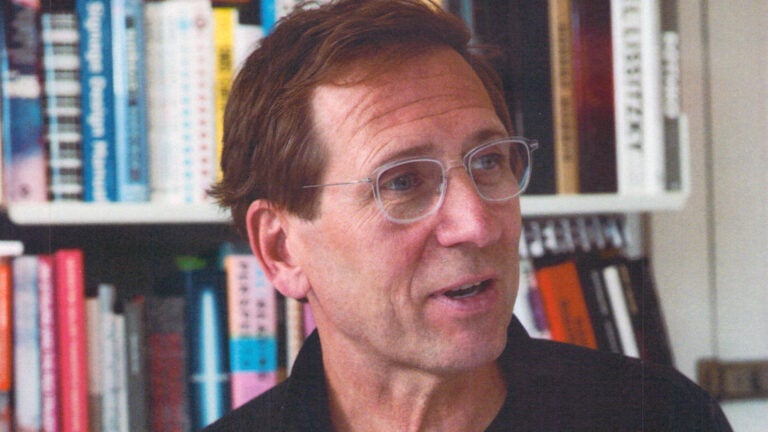

Brett Steele attended art and architecture schools on the West Coast before founding his own architectural offices in New York and London. (Photo/Courtesy of Brett Steele)

University

World-renowned architect Brett Steele named new dean of the USC School of Architecture

Steele brings a global perspective to the practical and academic study of architecture.

Architectural scholar Brett Steele has been named the new dean of the USC School of Architecture, effective Feb. 1. Steele will also hold the Della & Harry MacDonald Dean’s Chair in Architecture.

“The interdisciplinarity of the work within the different programs, faculty and curriculums I’ve been involved with in my career is something I very much look forward to building upon in coming to USC, which, as a school of architecture, is remarkable for the breadth and depth of its portfolio of creative activities and professional interests,” said Steele, who comes to USC after serving as dean of the UCLA School of the Arts and Architecture since 2017.

“Brett Steele’s collaborative leadership is a perfect fit for our School of Architecture,” USC President Carol Folt said. “One of the things that impressed me most when I met him is that throughout his career, he has inspired creative and inclusive ways of thinking that bring architects closer to their communities — and that keep innovative design and research top of mind. He’s a dynamic addition to our architecture community.”

At UCLA, Steele oversaw 14 degree-awarding programs in four academic departments, two world-renowned museums (the Hammer Museum of contemporary arts and the Fowler Museum at UCLA for world arts and cultures) and the Center for the Art of Performance.

Steele led several initiatives that resulted in the school’s highest enrollment of students from diverse backgrounds, the revision of curricula to be more inclusive, and increased civic engagement, especially with communities often underrepresented in higher education.

He also helped lead successful fundraising efforts to improve the school’s facilities and enhance student and faculty support, as well as expanding the school’s footprint in Los Angeles, including the acquisition and renovation of the UCLA Nimoy Theater in Westwood and the UCLA Margo Leavin Graduate Art Studios in Culver City.

New dean of USC School of Architecture: An interdisciplinary approach

For Steele, the interdisciplinary nature of his work at UCLA proved to be a rewarding aspect of the job.

“The exciting part of the role for me was the chance to work in four very different creative fields on the academic side of the house, which includes not just architects and urbanists, but also artists, designers, makers, performers, dancers and scholars of all kinds related to the arts,” Steele said.

He’ll bring that interdisciplinary approach to USC’s School of Architecture as its newest dean.

“One of the things I learned early on about USC is that the kind of interdisciplinary collaboration that is so important to creative fields and professions of all kinds is built into the culture of the campus,” Steele said. “I can already think of ways in which we can be a valuable creative partner to work that’s taking place all across campus, and that relate to President Carol Folt’s ‘moonshots’ and some of the big ideas that are leading USC forward today, but also the opportunities that exist between us as a school of architecture with the other creative schools on campus.”

Steele will also draw from his experience serving as a member of a variety of international review panels that explore the challenges architecture schools face and changes within related fields and professions.

“The key takeaway for me has been the urgent need we in schools should always be aware of and address, which is the ways in which architecture schools need to continue to adapt and evolve with the world around them,” Steele said.

A global lens

The first in his family to attend a university, Steele grew up in Oregon and Idaho, attending art and architecture schools on the West Coast before founding his own architectural offices in New York and London, where he became a naturalized British citizen. While in London, he graduated from the Architectural Association School of Architecture before being elected as the 19th director of the AA school, one of the world’s most influential schools of architecture.

As director of the AA, Steele oversaw all full- and part-time academic programs, the association’s global membership and two subsidiary companies: AA Publications and the Hooke Park Educational Trust. Steele’s contributions during his tenure include the launch of a worldwide visiting school that operated dozens of schools across five continents and in more than 50 cities. Steele was also instrumental in the creation of a PhD by design program, new master’s programs and an MA/MFA program exploring spatial performances and constructions throughout phases of research, design and production.

Before becoming director of AA, Steele also designed and led the school’s first accredited Master of Architecture program, the AA Design Research Lab, an impactful, team-based interdisciplinary studio he led for eight years.

“The USC School of Architecture has a proud history of pioneering faculty, students and alumni,” said Andrew T. Guzman, USC provost and senior vice president for academic affairs. “Dean Steele brings with him a rich background as the former dean of UCLA’s School of the Arts and Architecture, former director of the Architectural Association School of Architecture and as a practitioner. He has a track record for expanding the horizons of everything he touches, and I am confident he is the best next leader to balance transformative change at the School of Architecture while honoring its strong tradition of excellence.”

The USC School of Architecture is Southern California’s oldest architecture school and the only architecture school attached to a private research-1 university on the West Coast. Founded in 1914 as a department, the school offers undergraduate and graduate degrees in the fields of architecture, heritage conservation, building science and landscape architecture. Dean Willow Bay of the USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism will continue to serve as interim dean of the school through the end of January.

A critical moment for architecture in L.A.

Much of Steele’s writing explores how the field of architecture has transformed globally in the past 150 years. His new role will involve shepherding USC through its uniquely evolving relationship with the city around it.

“I feel incredibly blessed and lucky to have spent my adult life in New York, London and Los Angeles, cities full of amazing artists and designers and architects, but also full of amazing audiences for that work,” Steele said. “One of my great hopes at USC is for us to build upon this amazing legacy of architecture that’s identified with this great school, but also continue to find ways in which USC plays a vital role in the building of those audiences surrounding architecture and landscape and conservation, and the making of the kind of cities which are genuinely possible here in ways in which it just isn’t in so many different schools and cities around the world.”

Steele is especially excited to be immersed in architecture, sustainability and infrastructure in L.A. as the city prepares to host its third Olympic Games in 2028. “This is a remarkable moment of optimism for all of us to engage and embrace,” he said.

Steele is married to Natasha Sandmeier, an architect who serves as the executive director of the Architecture and Design (A+D) Museum in L.A. and as an adjunct professor with UCLA Architecture and Urban Design. The couple live in L.A. with their children, Stella and Leo.

Novel predictor of prediabetes in Latino youth identified in USC study

Research could lead to a new way for doctors to identify Latino children and teens most at risk of developing prediabetes.